The hardest thing in the world is simplicity.

— James Baldwin

Rethinking the Typical Goal of Family Learning Efforts: Meeting the Demands of Inherited Complexity

In the 5 Capitals model of what constitutes family wealth, “learning capital” or “intellectual capital” generally relates to the knowledge or learning of the family and its members. As I’ve reflected on this capital recently, I’ve been thinking about it as whether the knowledge of the family meets the knowledge demands of the family’s context. Put differently, the question isn’t whether the family knows a lot in the abstract; the question is whether they know and are learning what they need to know given the demands on knowledge created by the business, wealth, enterprise, or governance structures, processes, and architectures they must navigate.

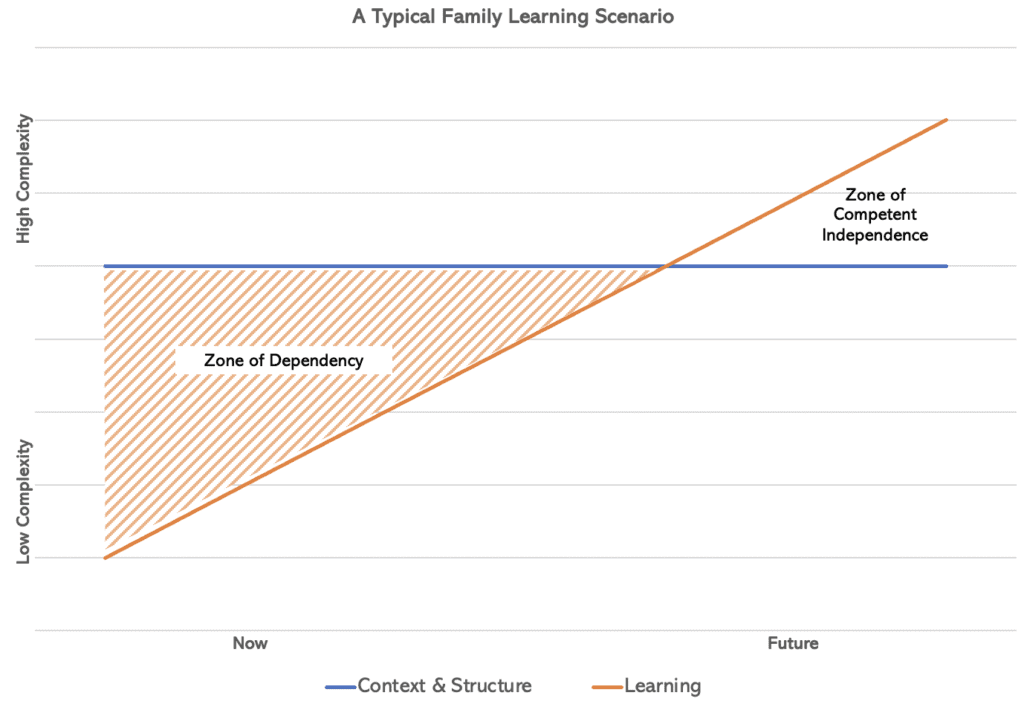

For visual thinkers, imagine a simple graph. The vertical axis represents complexity of context or structure (low to high). The horizontal axis represents time (moving to the right). Figure 1 assumes a relatively high level of complexity in the family’s context. They have an operating business to run, or more than one. There is a family foundation with staff and grantee relationships to manage. Their financial capital is invested in complex financial products, direct investments, or is actively managed as opposed to a passive indexed portfolio. If the family’s level of knowledge is relatively low, its learning must increase over time to meet these knowledge demands inherent in the complex context.

Figure 1

In many family learning discussions there seems to be an embedded assumption that “more learning is needed and more learning is better.” Of course, at some level human beings probably always do better with more knowledge and learning than with less. But in a family enterprise system, where family learning is seen as an imperative in order for the family to be able to govern its affairs and navigate its world, the fundamental question should be how the family’s “learning capital” or “intellectual capital” (or knowledge base) measures up against the demands of its context.

When a family doesn’t know enough to handle its environment, as in the left portion of Figure 1, it can be quite stressful. This is akin to asking a ten year old to drive a car or a layperson to land a jumbo jet. I call the shaded triangle the “zone of dependency.” When the family’s knowledge or intellectual capital is less than the demands of their environment, they are likely to feel dependent on others–advisors, professionals, etc.–to handle their affairs. To reduce the disparity between knowledge level and the context’s complexity, one of two things must happen: either the family must learn a great deal or the context must change.

A Central Goal of Family Governance & Leadership: Calibrating Complexity and Learning

Just as Figure 1 illustrates the (often implicit) goal of family learning efforts, it also highlights what should be a key goal of family governance and leadership: to determine the appropriate level of contextual complexity for the family.

This is a somewhat unusual way to frame the purpose of governance. Generally we think that family governance is about making decisions, resolving conflict, and communicating effectively among family members. Each of those things is how family governance operates, or the type of tools that are needed to make governance happen. But at base, what is the purpose or goal of family governance? What should a family be deciding, exactly?

I have long argued that family members–particularly inheritors–need to focus on their own sovereignty; on shaping the architecture of the system around them so that it meets their needs, interests, and priorities. In family enterprises, family members don’t just inherit financial capital–they inherit governance structures, committees, philanthropic boards, and myriad other structures that they have to manage. A key question for their own well-being, sense of agency, and personal sovereignty in the world is whether they feel that that architecture meets their needs. In particular, is it overly complex for their level of knowledge, or their family’s level of knowledge, or for the level of knowledge that they can realistically collectively achieve?

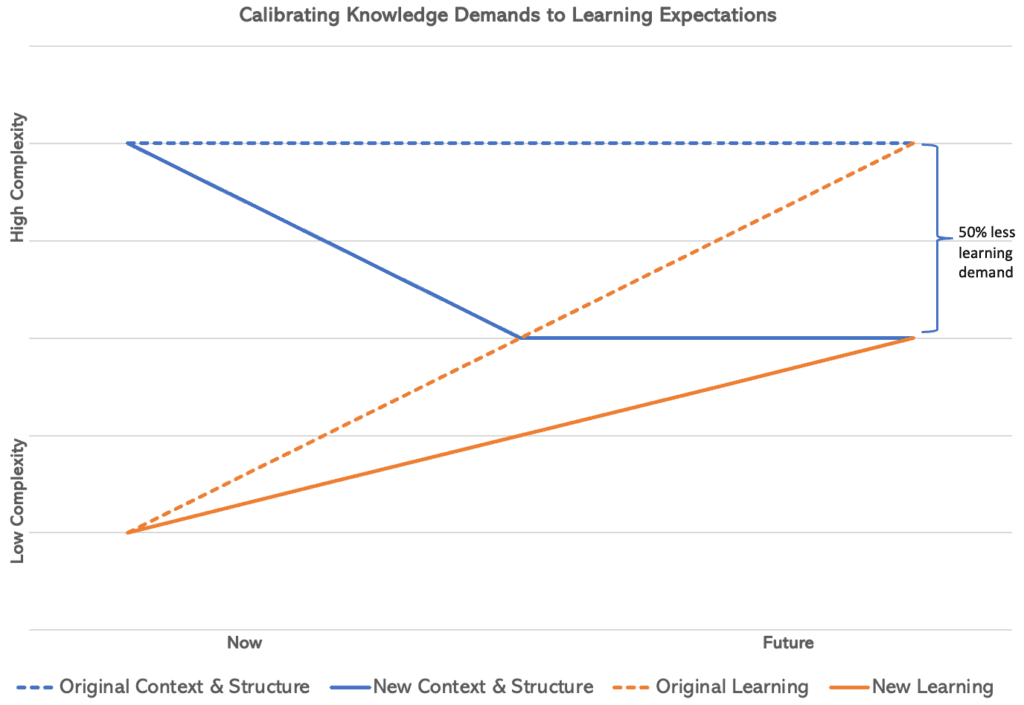

Put simply, Figure 1 shows a family striving to increase its learning to meet the static demands of its context. But the graph in Figure 2 shows another approach: decrease the level of complexity. As a collective, family members must decide: how will they calibrate complexity (downwards) and/or learning (upwards) so that they are able to effectively manage their context?

Note that in Figure 2, the slope of the family’s learning curve changes as complexity drops. They have less (half as much) to learn over the same period of time. The family’s dependency on advisors and professionals also drops dramatically during this learning period. All of this is likely to reduce stress and increase overall well-being.

Figure 2

Enterprising families often have learning committees that arrange family meetings and oversee the family’s overall approach to learning. But the questions posed here are a bit more fundamental. Rather than take their context–or the structures around them–as given, and set learning goals based on those givens, sometimes a family should instead consider reducing the complexity of that context to make their family learning aspirations more achievable or realistic. If there are no family members with (or likely to get) business experience, running a complex operating company may not be in everyone’s best interest. Perhaps it is time to sell. If none of the family has a legal background, very complex trust structures may not be the best idea. If family decision-making is strained or there is little governance experience in the family, starting a private trust company or designing a set of complex governance committees may be unwise. Complexity is not fixed; it is a choice.

Four things are worth mentioning here. First, often one generation inherits complexity from a previous generation. The structures, boards, committees, and other architectures of a first generation founder may not work well for her second generation children or third generation grandchildren. I see families struggle to populate structures that were designed by and for someone that is now gone. And/or, sometimes one sees a current governing generation building structures that their children are unlikely to find manageable. Again, there are choices here to be made.

Second, calibrating contextual complexity to realistic learning expectations does not imply some sort of defeat or failure. Just because grandmother enjoyed running her operating business, it is not a shortcoming for a set of grandchildren to decide that their interests, passions, or knowledge level do not fit well with continuing that themselves. Honest, mature, clear-eyed, realistic assessment of the calibration between contextual demands on knowledge and the family’s ability to acquire such knowledge is all that a senior generation or family founder can really hope for. If a future generation realizes that bringing down the level of complexity will best serve the family’s well-being overall, that is most likely a wise choice.

Third, calibrating complexity changes the quality of a family’s learning, not just the required quantity. Contextual or structure complexity generally pulls a family’s learning towards technical subjects like investing, accounting, trusts, and estate planning, which may then take up all the airtime and preclude learning about more qualitative subjects like one’s feelings about or relationship to money, communication and relational skills, or values and purpose. As Ruth Steverlynck put it to me, “learning that is less about knowing and more about feeling or being.” One of the hidden costs of complexity is that it may skew a family’s efforts away from such qualitative topics, because there “just isn’t time for that” given the technical or quantitative learning demands of the family’s situation. Likewise, one of the hidden benefits of simplification can be to free up more space for these explorations of human capital, social capital, legacy and purpose.

Fourth, I have written about the challenges of integrating inherited financial capital and family structures into one’s life. Often inheritors feel that “all of this is happening to me.” Such sentiments are often, in my view, a clue that the contextual demands on the person or family are not well calibrated to the knowledge base of that family. To achieve a more peaceful, fluid state will likely require bringing the complexity of the context down somewhat to match whatever realistic expectations for learning the family creates.

Figure 2 does not imply that it is always better to reduce complexity and the slope of a family’s learning curve. Sometimes a family can and should choose to maintain a complex enterprise or set of structures to achieve various goals. They may enjoy the learning challenge posed by the demands of their inherited context. The point is that there should be choice and realistic expectations. The slope of both lines in these graphs should be discussable. Do we want the complexity we have now? What complexity could be reduced and how? What would the costs and benefits of simplification be? How much do we want to invest in learning, and how likely is it that we can get into a zone of competent independence in a reasonable time? These are the conversations that families need to have.

A Central Goal of a Family Office: Managing Both Complexity and Learning

This brings us to the role of the family office professionals that serve a family. As I have written elsewhere, too often family offices focus exclusively on managing financial capital and legal risk, without attending sufficiently to the family’s overall well-being. In the framework we are using here, such advisors may assume that the contextual complexity of the family’s enterprise is fixed and given, rather than seeing it as something that can be changed over time. They are there to “run the machine,” not to fundamentally reassess whether the machine as it exists is in the family’s best interests. They may therefore stress family learning, urging the family (sometimes with fear) to “prepare themselves” for the complexity they must deal with, as if an increase in the family’s learning capital or intellectual capital is the only possible lever to pull. They miss that the level of complexity itself can be altered through planning and hard work.

A massive industry has grown up around helping “next gen” inheritors learn and prepare. There are countless family wealth consultants, workshops, next gen retreats, etc., with such offerings. There’s nothing wrong with these services, and I encourage these efforts. And, it is critical to remember that generally the consultants, banks, law firms, and other experts offering them do not have the power, access, or expertise to consider altering the basic structures of the family’s context. Put differently, they focus exclusively on the slope of the learning curve because they do not have direct influence over the slope of the complexity curve. (This does not absolve such firms or advisors of the responsibility to try to address the structural complexity facing a family. They just seem to focus on learning because it is far more within their sphere of control or influence.)

A family office, however, does (or should) have influence over complexity. (In fact, that is one of the primary implicit reasons that families set up private offices rather than relying on outsourced services.) A basic goal of a family office should thus be to manage both the complexity of the family’s enterprise and the family’s learning efforts to achieve an equilibrium in which the family’s members can flourish. Just as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s great work on Flow suggested that optimal flow requires matching one’s abilities and the challenge of the task at hand (too hard and one will be frustrated and quit; too easy and one will be bored), a family office must work with a family to bring complexity and learning into connection over time. The two lines in our graph must cross for the family to feel able to live in its environment successfully. How they cross is a project for both the family and its family office advisors.

As I’ve written elsewhere, it is easy to imagine that a family determines the “goal”–such as “less complexity”–and a family office staff simply executes on that goal. Culture and structure are far more interdependent than that, however. For our purposes here, it is important to recognize that family office staff may be resistant to diminishing complexity in the system. Their jobs may be at stake. If a family wants to eliminate an operating business, reduce the number of trusts, radically simplify an investment portfolio, or otherwise lower the level of complexity in their context, there may be far less need for family office assistance. Less complexity may be threatening to the family office staff.

In addition, it is often the case that family office professionals don’t see the complexity around them, or don’t find it nearly as difficult or stressful as the family members they serve. The professional staff most likely has the technical expertise to make sense of such complexity. It may be invisible to them, or at least not something they think much about reducing. They may not connect emotionally to the stress, helplessness, or feelings of inadequacy that family members experience. On the contrary, complexity may feel like creativity to them, as they show their expertise by crafting intricate structures, estate plans, trusts, and investments.

I don’t mean to imply that family office professionals (or other advisors) are ill intentioned or likely to consciously act contrary to their client’s interests. The vast majority take their roles as fiduciaries extremely seriously. I only highlight that addressing complexity in a family enterprise system may be complicated by these sorts of issues, because the staff members tasked with doing so are themselves participants in, and benefiting from, that system. They will have to serve as the true professionals they are–putting their clients’ interests and needs first–to have these conversations and meaningfully address the complexity curve.

Finally, as mentioned, a family might reasonably choose to maintain a high level of complexity in its financial, legal, and other affairs, and to rely on its professionals to handle that complexity. That is a possible outcome of this kind of discussion and analysis. But families and their advisors must consider other possible outcomes as well. There are many ways to calibrate these two variables: contextual complexity and family learning capital. Ultimately, the well-being of the family will depend on the success of such efforts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a story. My wife and I have kept a Jade plant for the last twenty years. For most of that time, it was healthy and beautiful; lush green leaves, strong branches. Six years ago, we got a new cat. Around the same time, the Jade began to deteriorate. We gave it more or less water, more or less light, and a new pot. Eventually we realized that the cat liked to knock the leaves off the jade and play with them. We put sticky tape around the plant to deter her. We squirted her with water when she got near it. Still, the Jade’s leaves got thinner and less healthy, its branches smaller and weaker. It didn’t seem like it would make it.

A year ago, we moved the Jade into my office studio, which the cat can’t access. Almost immediately, the Jade began to perk up. Tiny new leaves began to appear, when there hadn’t been a new leaf in years. The plant got more and more robust, eventually even growing two new stems from the soil. After twelve months, it was a flourishing Jade plant again.

I didn’t have to do much of anything to achieve this result. No special watering, no special nutrients. Just remove it from the cat’s reach, and it had what it needed to succeed. The moral of the story? Context matters. Sometimes it’s just about getting away from the cat, and the plant–or the individual or family–will flourish far more easily.

I am grateful to Jim Coutre, Mary Duke, Ruth Steverlynck, Matt Wesley, and Rick White for comments on an early draft of this post.