A Zen master asks a wandering monk, “where are you going?”

“I’m wandering on a pilgrimage,” says the monk.

“What’s your purpose,” says the master.

“I don’t know.”

“Not knowing is the most intimate,” says the master.

The monk instantly understands.

— Case 20, The Book of Serenity

I was recently asked to explain this famous Zen koan, or teaching story. At about the same time, I was also asked to give a short talk in another context on everything I’ve learned in the last twenty-five years about teaching and practicing good listening. (I spent many years as a law professor teaching conflict resolution, negotiation, and managing difficult conversations, and even more years consulting to CEOs and others on these issues.)

The timing of these requests was perfect, as the two topics are in many ways the same. To explain that, let me begin with a graphic that I put together for the listening discussion.

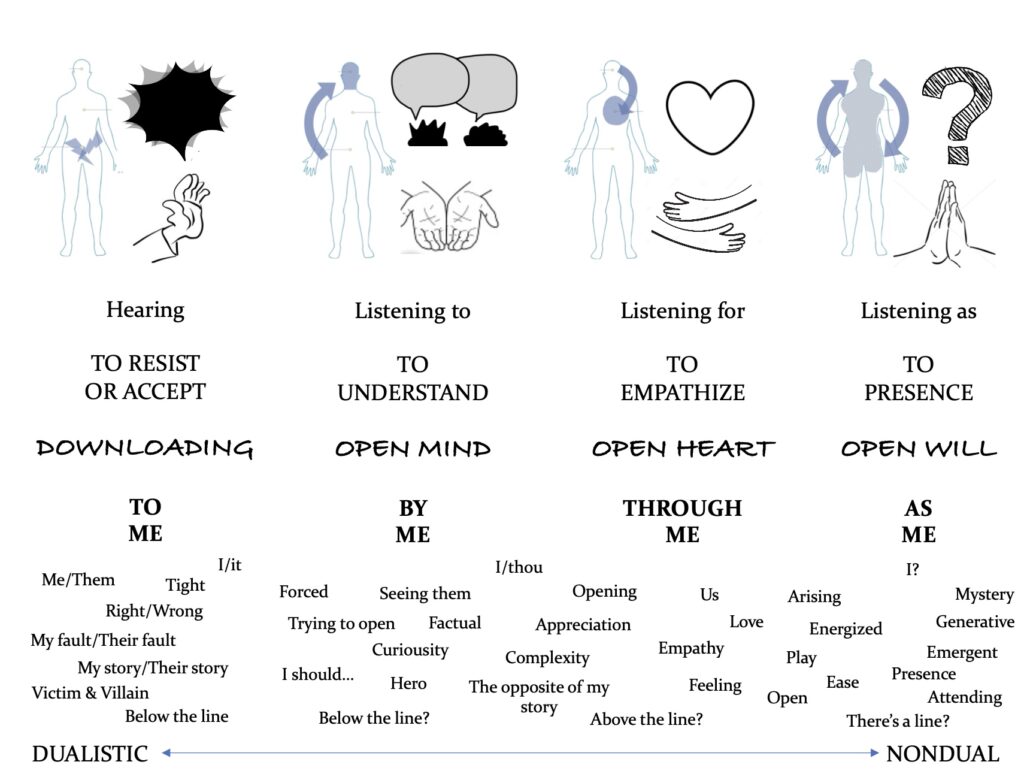

This graphic borrows from various thinkers to try to describe a spectrum of listening, from mere hearing (on the left) to full, present, open listening (on the right). In particular, Otto Scharmer’s “Theory U” or listening levels are reflected here, as are concepts from 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership, Difficult Conversations, and elsewhere. And, I believe that there is a lot of novelty to ingest in this synthesis of these different approaches to listening as a practice and path.

The core of what I want to say about listening at this point in my life is that deep listening becomes a non-dual spiritual practice, rather than a pragmatic “tool” to be used to persuade or build relationship with others. Far to the right on the diagram above, one is no longer “listening to” “the other.” I, other, and task have fallen away, as one sits in presence with another and attends to what arises. We are in communion more than anything.

For many, this description may feel opaque and “out there.” I’m ok with that. I’m guessing many readers of this blog won’t feel that, however. Instead, seeing these different types of listening laid out in this way will make some degree of sense intuitively. But let me go through them one-by-one for clarity:

- We begin with simple hearing, which is often a very dualistic experience in which our inner voice is either resisting or giving in to the information that is happening “to us.” In this constricted place, we are often consumed by dualisms: me/them, right/wrong, my fault/their fault, my story/their story, victim/villain. We are likely to be reactive (“below the line” in conscious leadership speak) and feel tight in our bodies somewhere–in the gut, the chest, etc. This is barely listening; more hearing, if that.

- We move on to listening to the other–trying to understand the content of what they’re saying, the story they’re telling, the argument they’re presenting. We may have an open mind, and be trying (“by me”) to listen as best we can. This is when people experience “trying to listen” or “trying to open,” which can feel (and be) oxymoronic. Physically we may feel movement from the conflict in our belly up into our head, where we may be able to get curious as we negotiate ourselves into a different “mind set.” All of this can feel (and be) a bit forced, but it may represent real progress and effort towards listening to understand.

- Then we have listening for the other–with an open heart, not just an open mind. The conversation may begin to be more fluid, less organized; more through us than “to” or “by” us. Empathy may emerge, along with love, play, ease. To be here, we are likely far less reactive, far more “above the line” (again, in conscious leadership speak), far more comfortable sitting with ambiguity and complexity. The dualities of right/wrong, my story/their story, me/them aren’t “wrong” at this point, but they seem less and less relevant. We are curious, yes, but more we are open. Genuinely open to the other person’s full experience, including their heart’s pain.

- Finally, as mentioned, we may move into open will, generative presence, emergent co-creation, energized attending. This is not happening “to,” “by,” or even “through” me. Instead, there is radical unknowing here, and a full body (gut, heart, head) experience of nondual presencing.

I could write or talk endlessly about all of this, but I will exit this by tying back to my Zen koan. After becoming clear on these types of listening activity, what is really clear to me is a missing piece that I never saw in all my years of trying to help others learn in this domain. That missing piece is the motivation that helps one move from left to right on this (illusory in itself) spectrum.

I have long worked with others to combat the “I’m right, they’re wrong” assumptions in their heads, and the dualisms of “it’s their fault” or “they intended to …” or “I’m the victim because…” The antidote, I (and others) have always offered to “right/wrong” thinking is curiosity. Can you get curious? Can you, just for a moment, genuinely negotiate your own mind into a place of curiosity about the other so that you can ask questions, empathize with their feelings, and see their point of view? Curiosity has been the counter to restricted thinking that exacerbates conflict, and the “goal,” I suppose, to being make one a better listener.

But … and here’s the missing piece … why be curious? What is it that it gains you? The answer, I believe, is beautifully captured by “not knowing is the most intimate.”

The Zen Koan highlights that only when we let go of our assumptions and preconceptions can we truly experience anything in its raw, unmitigated, unvarnished form. When we look at an oak tree, do we see the tree, or do we only see the reduced mental representation that our mind instantly creates — the “tree.” We “know” what that is; we know that it has a trunk and branches and leaves. And so we don’t really see it at all — we see a schematic of “tree,” missing huge amounts of its actual beauty and uniqueness. This is why so many of us can’t draw or paint — because we can’t see what’s directly in front of us. We draw the reduced schema of tree — the stick figure — because “that leaf should be green” so we draw green. But really, at the moment we’re looking, that leaf is gold, or purple, or brownish blue, or all of the above. Only an artist can see the tree as it really is, before conception, projection, and assumption.

“Not knowing is the most intimate” asks us to be artists in all respects in our lives. To see not just a tree, but each other without our assumptions, attributions, and projections. To see the other and not know who they are, what they’re all about, what we think they’re trying to do, what our story of them is. Just to sit with them in raw presence and let whatever unfolds unfold. And, perhaps more challenging, to be with ourselves without preconception–to truly be in presence with another requires us to truly be in presence with ourselves: to let go of who and what we think we are, just for a moment.

And so the missing piece is intimacy. Because the koan has it exactly right — if (and it’s a big if) our reduced schema of self and other can drop away and we can just be in presence with each other, then we immediately find a level of intimacy, connection, co-creation, and mutuality that is both exceptional and what we truly desire. Humans are social creatures; there’s almost nothing we crave more than true connection. That is the one thing that we might be willing to give up our “rightness” for–the one thing that can motivate real curiosity. It’s a far more powerful experience, and motivation, than just listening to or listening for another. It is paradoxically dropping through both our self story and our story of the other completely, and listening in true not knowing, that is the most intimate.