Many multigenerational enterprising families have learning goals: to bring younger family members up to speed on the workings of the family business or financial assets; to create family cohesion around a vision or sense of purpose; to educate beneficiaries about the workings of trusts, family partnerships, a private trust company, or other legal structures; to bring family members into the family’s philanthropic efforts; and so on. These goals may be more or less articulated, but they are often evident in the way a family sets their agenda for family meetings and other learning events.

My focus in this post is on how those goals should inform a family’s long-term learning plan. As a long-time educator, I am used to the notion of a curriculum–a sequence of courses that together lead a student through a deepening understanding of an area of study. To become expert at something, you don’t just begin with an advanced course in the subject (e.g., Econ 300). Instead, you begin at the beginning, learning introductory material first and then building on that foundation through a sequence of learning experiences that both repeat and reinforce prior learnings and add increasing complexity and nuance.

Families serious about learning should develop a curriculum for their family members that is thoughtful, aligned with their goals and values, and transparent. Otherwise, family learning events such as family meetings may feel scattered or lacking in purpose, and most likely will not maximize the time used to further the family’s learning. In this (rather long) post, I explore how to do that, and in particular how to use the “Five Capitals” model to structure a family learning curriculum.

A Note on Privilege

Before diving into curriculum design, I think it is important to address the issues of privilege and inequality in the context of family wealth and family learning. The very thought of a wealthy or business family designing a “family learning curriculum” may seem so elitist as to be offensive. Members of well-off families already enjoy tremendous social and educational advantages; they are often among the most educated members of society. What more do they need in terms of “learning,” education, or curriculum?

There is merit to these concerns, and they deserve real conversation both within families and among family advisors and family office professionals. To ignore them is to bypass some of the critical questions of our time–the very questions often on the minds of family members asked to participate in family learning experiences. I have heard from many family clients that they dread nothing more than telling a friend that they are going to their annual “family meeting.”

And … my own experience of working with business families has been that anyone concerned about such social, economic, and privilege issues should ultimately end up advocating for more, not less, family learning and education in such families. Only by acquiring awareness, knowledge, skills, and insight can family members in privileged families come to terms with their good fortune, have meaningful conversations about their financial capital, and, for some, make decisions together about how to use it to make an impact in the world. As Chuck Collins has written in his book Born on Third Base, “those … in the top 1 to 5 percent of the planet’s wealth holders … have an important role to play in the transition to the next phase of human evolution.” Only by “suspend[ing] the economic class hostilities long enough to consider what would move humanity forward,” he writes, can we really engage all of society, including the very wealthy, with our deeper values and vision to address the social and global problems of this age.

I thus assume that a reader of this post can see the benefit–to individuals in these families, these families as a whole, and society generally–of a family learning curriculum for a business, enterprising, or wealthy family. Some may not, but I very plainly do.

Some Background on Curriculum Design

Although I have done it for many years, I do not claim to be an expert on curriculum design. As shorthand, therefore, I will just make a few observations from my own experience that families and their advisors might consider as they begin to create a learning curriculum.

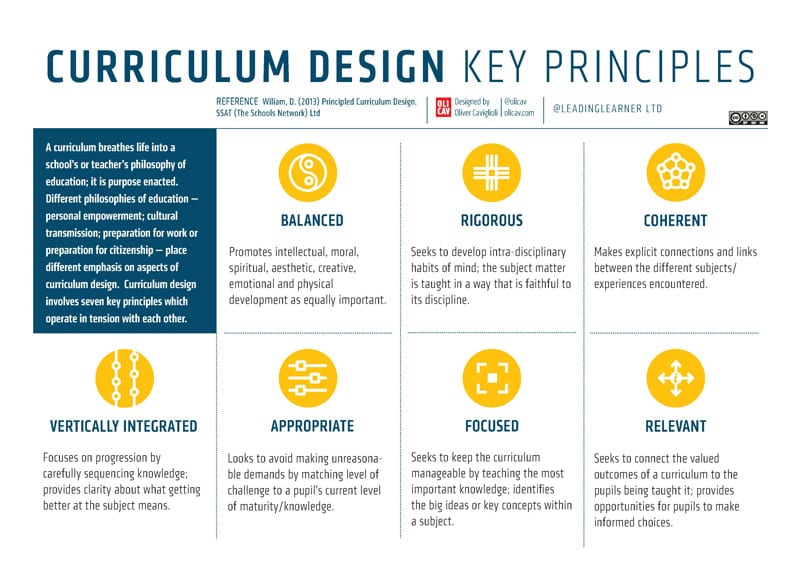

This simple graphic (from Leading Learner) highlights a few key principles for curriculum design. A good curriculum is, as the graphic suggests, “purpose enacted.” It should at least exhibit these seven qualities:

- Balanced: As the graphic suggests, a curriculum should promote different spheres of learning, including intellectual, moral, spiritual, emotional, and physical well being. Those familiar with the Five Capitals model (which we will explore below) will instantly connect this goal of “balance” to those capitals–in my view, a family learning curriculum should work across and between the Five Capitals simultaneously.

- Rigorous: Family learning should be fun and engaging, but it is also serious work. If a family is truly committed to the flourishing of its members, the work should be deep. As the graphic suggests, the curriculum should develop “intra-disciplinary habits of mind.” To me, this means going deep enough in each subject area that learners internalize that subject’s architecture and mores–the core of that subject’s knowledge.

- Coherent: The subjects covered in a curriculum do not exist in isolation–they are interdependent and connect at various points. A curriculum should make this transparent and explicit, so that learning experiences are not fragmented but instead make sense as a sequence and a whole.

- Vertically Integrated: Within each subject covered, there should be a learning sequence that begins at the beginning, moves through the middle, and advances to the more expert. Learners should know what the “end” of that subject looks like–what “getting better” means. They should also be able to imagine getting to that end through a series of reasonable steps. In other words, they should be able to see what the target is, even if that target is off in the distance, and understand how they get from their current state to the target state through a sequence of learning experiences or actions that they can reasonably imagine undertaking.

- Appropriate: This design principle is particularly important in family learning, where you may be designing for participants that vary widely in age (10 to 85!), expertise (one person running the family enterprise, another an artist with limited financial experience), and interest. To create engagement, learning experiences must meet each learner where they are, and bring them along to a higher understanding of the topic in question. This is one of the most interesting challenges of family learning curriculum design.

- Focused: If a family or family advisor lists all of the possible topics, questions, issues, and frameworks that the family could learn about, the list will most likely be completely overwhelming. A family learning curriculum should focus, selecting those things that need to be learned first, those that can be attended to later, and so on. As the graphic suggests, a curriculum must feel manageable. This can be somewhat at odds with the idea of setting out the target (see above); it underscores that the curriculum must articulate how the target can be achieved in a focused and manageable process.

- Relevant: Family advisors or family office professionals often complain that family members are not engaged with family meetings or family learning. Just as often, the problem is relevance: is the material being presented actually relevant to the learner now? Explaining how a private trust company or a Grantor Retained Annuity Trust works might seem important, but is it what this learner actually loses sleep over? Will it help this family member today to live a better, healthier, more fulfilling life? Starting with that question leads to learning material that is relevant to the person, and therefore to engagement and purpose.

I find these seven design principles very helpful in thinking through a curriculum. Each is a powerful guide. In addition, I will add three more background thoughts on curriculum design.

First, connecting individual learning and a family curriculum. Some will eschew the idea of a family curriculum at all, preferring to design individual curricula for each family member. I don’t disagree. Tailoring to each individual is important. At the same time, I can’t imagine how to design an individual learning plan with a family member without having an overall sense of the terrain that the family wants to cover as a whole. Each family member may take a different path through that terrain, but a curriculum does not preclude that. Instead, a curriculum is a map of the terrain as a whole, from which individual plans can draw.

Second, co-creation of a family curriculum. Often a family recruits advisors, family office professionals, or an outside consultant to help design a learning curriculum or an isolated learning event (such as a family meeting). The family may be too busy to create such experiences on its own, may recognize that it does not know what it does not know, or may seek outside help because it understands that it lacks the expertise to “teach itself.” The reality, therefore, is that a family learning curriculum will often be designed for a family, not by the family. That said, co-creation of the learning curriculum is important. Although an initial plan may come from an expert, the family must slowly–perhaps over years–come to understand that plan and make it their own through modifications and re-prioritization. This takes more than just one conversation (e.g., “here’s the plan; sound good?”). It requires ongoing opportunities to look at the learning curriculum, assess it against the family’s goals, and revise.

Spiraling Through a Curriculum

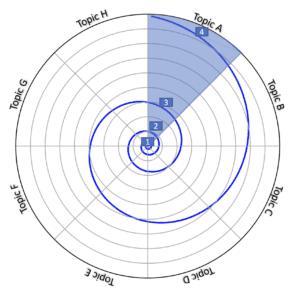

Third, spiraling repetition. Most human beings cannot learn something on the first try. Instead, it generally takes several–some will say up to seven–repetitions of a concept or skill before a person really learns it fully. Rote repetition, however, is boring and frustrating. In thinking about a curriculum, I draw on the image of a spiral–which is so prevalent in nature. If you imagine starting at the center of a spiral, as you go around the spiraling path you return again and again to the same general area of the spiral (say, the shaded Topic A), but never to the exact same point. The metaphor is powerful: you might first learn a simple concept; you then move on to other subjects or concepts; you then return to the first idea, but in a slightly more advanced or nuanced way; and so on. In the diagram above, for example, you learn something about Topic A at Point 1, then move through other topics before returning to learn more about Topic A at Points 2, 3, and 4. As you spiral through a curriculum, you return again and again to reinforce earlier learning, but without rote repetition–each time gaining altitude, so to speak, and thus advancing. You also learn about the “neighborhood” around Topic A–how A connects to B and also to H. You begin to see interdependencies between topics, while simultaneously advancing in each unique topic. And you never move from 1 to 2 to 3 to 4–or very rarely. Put simply, real learning does not happen in a straight line. It requires acquiring knowledge in connected domains through repeated experiences over time.

Some Background on the Five Capitals

Having explored a bit about curriculum design, let’s turn to the heart of the Five Capitals model, which I have been using as the foundation of family learning curriculum creation.

Jay Hughes pioneered the idea that a family’s wealth is not limited to, or even primarily about, its financial capital, but is instead made up of financial capital plus other qualitative capitals. These qualitative capitals have been sorted, organized, and labeled in many different ways since Jay’s initial discussions in his written works. I will present them here as I currently describe them–others may call them slightly different things or cluster them into slightly different categories.

![]()

About These Icons: I use the five icons (shown above), as well as the colors associated with each, to represent the five capitals. I find that consistent graphical iconography can be very helpful in making a learning curriculum accessible. For visual learners, in particular, iconography may be easier to remember than textual labels. You are welcome to borrow or develop these icons as you see fit.

The qualitative capitals break down into four general categories. Human capital is the most basic: the family’s “wealth” really comes down to the question of whether each individual family member is flourishing. Are they physically and emotionally healthy? Are they secure in their person, relationships, and career? Can they give and receive love? Do they have interests and passions that drive them? The family’s human capital is the collective flourishing of its members along these multiple dimensions.

Learning capital, which Jay and others have called “intellectual capital,” centers on each family member’s commitment and ability to learn over their lifetime. Does the family have a learning culture? Are its members open to learning experiences, curious about the world, engaged in intellectual exploration, and eager for information that challenges their respective worldviews? Does the family have the knowledge it needs to succeed in a competitive and changing world, and to meet the internal and external challenges it will face over time? Are the entities that support the family, such as a family office, learning organizations that continually seek to grow their own learning?

Social capital is the relational strength of the family and its ability to govern itself, make good decisions, communicate, and excel together. Can the family manage conflict? Can it negotiate amicably through differences, talk about difficult subjects, and honor hurts and other strong emotions? Do family members have strong relationships outside of the family–in work or in personal matters? Does the family have good decision-making and governance structures in place, and, more importantly, does it have a family culture and the interpersonal skills needed to actually use those structures effectively?

Legacy capital, which some call “spiritual capital,” is the family’s reserve of purpose, vision, and spirit. Does the family feel connected to its history and to the ancestors that gave it not only financial capital (in many cases) but the human, learning, and social capital that helps it succeed? And can the family look forward into the future together, imagine the impact that it or its members hope to have in the world, and create that legacy that future descendants will in turn inherit?

Finally, financial capital is both the array of financial assets that a family has and the knowledge it gains about how to use, preserve, or grow those assets. This includes traditional personal finance topics (e.g., budgeting, investing, etc.) as well as basic economic concepts (e.g., how interest rates work, how the stock market functions, what impact investing is). It also includes, in my view, the “softer” questions of how each family member relates to financial capital. Can money be a positive force in each family member’s life, and if not, why not? What work is needed to fully integrate financial assets into each person’s life in a way that is healthy and generative? All of this is the financial capital of a family.

A Five Capitals Family Learning Curriculum

Using the five capitals as the basis of a family learning curriculum allows for a plan that is both comprehensive (e.g., covering the terrain fully) and organized (e.g., not a jumbled and confusing array of concepts). The five capitals, in other words, help with keeping a curriculum balanced, coherent, vertically integrated, and relevant (per the design discussion above). As a family or family member spirals through a five capitals curriculum, they can see the different areas in which they will develop while simultaneously understanding that there is vertical depth to be mastered in each of these five domains.

Obviously, such a curriculum must be tailored to a given family’s history, culture and background, its business and financial situation, and its unique goals, vision, and purposes. That said, here are some questions and topics that a five capitals learning curriculum might cover.

These are learning topics that bring the family into clearer understanding of the problems and opportunities presented by preserving financial and human capital over multiple generations. They include:

- Background on the Five Capitals Model

- What are the four qualitative and one quantitative capital?

- Understanding the “family balance sheet” across all five capitals

- Understanding the problems created by myopic focus on financial capital

- Why human capital development is as or more important to the family and the business than financial capital management

- Why lifelong learning matters, and why it matters to be a learning family

- Understanding the family’s learning curriculum: 2-3 years of getting prepared to learn together; 2-3 years of getting prepared to make decisions together; 2-3 years of getting prepared to be owners together

- Understanding that every individual family member can and should increase the family’s wealth by growing the four qualitative capitals, even if they are not personally focused on growing the family’s financial capital

- The life cycle of family enterprises

- The Three Circle Model and the different roles and responsibilities of owners, managers, and family members

- The Controlling Owner to Sibling Partnership to Cousin Consortium model and how each phase differs

- The role of each “rising generation”: the importance of each generation being generative

- Risks

- The shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations proverb, what it means, and what it doesn’t mean

- Understanding internal challenges (transition, dependence, insecurity, poor decision-making)

- Understanding external challenges (war, social unrest, climate change, political stagnation, punitive taxes)

- The risks (in both directions) of getting the balance wrong between “binding together” and “being separate”

- The long-term dangers of taking too much or too little financial risk

- Books and Resources:

- Hughes, Family Wealth

- Hughes, Massenzio & Whitaker, The Voice of the Rising Generation

- Hughes, Massenzio & Whitaker, The Cycle of the Gift

- Williams & Preisser, Preparing Heirs

- Gersick et al., Generation to Generation: Life Cycles of the Family Business

- Lansberg, Succeeding Generations

- Collier, Wealth in Families

- Hausner, The Legacy Family

- Whitaker, Wealth of Wisdom

- Grubman & Jaffe, Cross Cultures: How Global Families Negotiate Change Across Generations

These are skills and topics to ensure that each individual family member is flourishing and enjoys physical and emotional well-being. They include:

- Physical and Mental Health

- Taking care of oneself: physical checkups, dental health, how to access the health care system, how to find a therapist or counselor, stress management, time management, managing health insurance claims, dealing with addiction, getting help

- Career Well Being

- The importance of work

- Finding meaningful work

- Career coaching: how to find, select, and work with a coach

- “Right livelihood” and what it means

- Relationship competencies

- Communication and negotiation skills

- Dealing with difficult conversations

- How to manage wealth-related fears and issues in core relationships

- Knowing how and when to get help

- How to hire and work with a therapist or mental health professional

- How to hire and work with a lawyer

- How to hire and work with an accountant

- How to hire and work with a financial advisor

- How to hire and work with a career coach

- How to hire and work with a mediator

- Integrating inherited wealth into a healthy life

- The importance of understanding dependence and subsidy versus enhancement

- The importance of differentiation, individuation, and boundaries

- Issues related to raising children in the context of financial wealth

- Privacy concerns

- Being honest about privilege, inequality, and the “bubble” or “marshmallow effect”

- Humility in the context of financial wealth

- The importance of cultivating gratitude

- Books and Resources:

- Stone, Patton & Heen, Difficult Conversations

- Fisher, Ury & Patton, Getting to Yes

- Goleman, Emotional Intelligence

- Duckworth, Grit

- Fredrickson, Positivity

- Dethmer, 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership

- Willis, Beyond Gold: True Wealth for Inheritors

- Willis, Navigating the Dark Side of Wealth

- Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success

- Levine, The Price of Privilege

- Gallo & Gallo, Silver Spoon Kids

- Taleb, Anti-Fragile

- Hausner, Children of Paradise

- Collins, Born on Third Base

These are skills and topics to help family members learn, both individually and together, and acquire the knowledge they need. They include:

- The importance of self assessment

- How do I learn and how do others learn?

- What are my strengths?

- What is my work style?

- What is my vocation?

- What is my personality?

- How do I handle Conflict?

- What is my stage of adult development?

- What are my spiritual inclinations?

- The importance of lifelong learning

- Learning in family systems and business systems

- Books and Resources:

- McCarthy, About Learning

These are skills and topics focused on improving the family’s ability to make complex decisions together and to govern the family enterprise over time. They include:

- Decision-making and collaboration competencies

- How to make decisions with others and deal with differences in perspective or priorities

- How to succeed on a team

- How to foster collaboration with another person or a group

- How to run or help run a meeting: agenda-setting and process design

- Governance competencies

- Transition versus succession

- Family meetings and why they matter

- What is a “family office”?

- What is a typical family enterprise governance structure?

- What is the difference between family enterprise governance and corporate governance?

- What is a family constitution?

- Typical decision-making challenges among sibling and cousin groups over generations

- The importance of structure: why structure is your friend

- The importance of culture: why culture eats structure for breakfast

- Understanding the trustscape

- What is a trust?

- What are the roles and responsibilities of a trustee?

- What are the fiduciary duties of a trustee, particularly the duties of care and loyalty?

- What are the roles and responsibilities of a great beneficiary?

- Understanding the option of saying “no, not yet.”

- What is the difference between a gift and a transfer, and why does it matter?

- Preparing for trustee/beneficiary meetings

- What is a private trust company?

- Onboarding of in-laws

- Why taking the adding of new family members seriously is important

- Prenuptial agreements and how to create a healthy prenup process

- The role that in-laws can play in family governance

- Common pitfalls for in-laws

- Employment in the family enterprise

- Why having rules or guidelines about family employment is useful over time

- What are the issues presented by family employment?

- Books and Resources:

- Goldstone, Hughes & Whitaker, Family Trusts

- Goldstone, Trustworthy

- Grubman, Strangers in Paradise

- Ward, The Family Constitution

- Dublin, Pre-Nups for Lovers

- Jaffe, Stewardship in Your Family Enterprise

- Marcus, Lives in Trust

These are skills and topics focused on the family’s history, stories, purpose, and vision, as well as on legacy, philanthropy, and giving. They include:

- Stories and legacy

- The importance of family storytelling and maintaining family traditions

- The family’s history and stories

- Connecting to ancestors: what is your true inheritance, beyond any financial inheritance?

- Your individual history and legacy: what do you want to be remembered for

- Family and individual purpose

- Does the family as a whole need or have a shared vision or purpose

- What vision or purpose does each individual family member hold?

- What does it mean to pursue a meaningful, just, moral, sane life in the context of financial wealth or a family enterprise?

- How to face and address issues of inequality, social justice, and environmental concerns?

- Impact investing and its role in family and individual financial management

- Giving competencies

- Individually: how to give meaningfully?

- How to measure the impact you’re having?

- Giving at different stages of life

- The advantages, disadvantages, and purpose of a family foundation

These are skills and topics focused on the investment of personal or family financial capital, and on the healthy use of and relation to financial capital. They include:

- Personal financial literacy

- Bank accounts, borrowing, and lending

- Investment accounts, brokers, and investment advisors

- Mortgages and why they matter

- Taxes

- How to save

- How to get paid what you’re worth

- How to spend wisely

- How to budget

- How to build your credit score

- How to think about home, car, health, life, and other insurance

- How to align your personal financial practices with your values

- Evaluating your sources of financial capital: where you work, where you invest, where you bank

- Evaluating your uses of financial capital: where you shop, how your consumer habits and choices express your values

- Evaluating the institutions and processes you use: whether your bank or credit union, credit card company, investment firm, insurance company, and other processors of financial capital align with your values

- Investment literacy

- Why invest at all

- The basic categories of investments

- How to measure investment performance

- How to choose and monitor an investment advisor

- What is diversification and why does it matter?

- What are alternative investments?

- What is social or impact investing?

- What is an allocation or portfolio model?

- Understanding goal-based investing

- Understanding the family enterprise

- What the family’s business or enterprise is and how it functions

- Estate Planning

- What is an estate plan and when should I create one?

- Should I have a health care directive?

- What is a revocable trust and should I have one?

- How to align an estate plan with your personal values

- Integrating financial capital into a healthy life

- Living an authentic life in the context of inherited wealth

- The importance of differentiation, individuation, and boundaries

- How to talk about inherited wealth

- Books and Resources:

- Chhabra, The Aspirational Investor

- Malkiel, A Random Walk Down Wall Street

- Marston, Portfolio Design

- Taleb, The Black Swan

- Graham, The Intelligent Investor

- Dalio, Principles (of economics, part II)

- Domini, Socially Responsible Investing

- Makower, Beyond the Bottom Line

- Savitz, The Triple Bottom Line

- Martin, Status of the Social Impact Investing Market

- Jackson, Prosperity Without Growth

- Wilkinson and Picket, Spirit Level

Putting It All Together

If you have read this far, I am grateful. To wrap up this very long post, I will simply say that all of the above is just a suggestion or pointer–a set of topics and questions that any family could consider and that any family would need to augment with issues specific to that family and its situation. Each of the five capitals is deep and important–thus the necessity of “vertical integration” (going deep into each capital) in curriculum design, as well as of “coherence” (identifying connections between the five capitals).

I will make a few final points in summary.

First, a family learning curriculum should look out 5 or 10 years into the future, and organize how the family will slowly acquire the knowledge and skills it needs to develop each of its five capitals. The lists above are long and complex. There is no way that any family could really learn a fraction of the material in any one of the five capitals in just a year or at a meeting or two. Instead, really developing true understanding in any of the capitals–and ultimately coming to understand their interdependencies and connections– requires time and sustained effort. Thus, in designing a curriculum, the “spiraling repetition” principle is key. Start with small bites from each capital. Then, over a period of years, build on those small bites by pushing for more knowledge and skills in each domain. Over time, once each family member has a baseline competency in each capital, allow family members then decide which capital or capitals really matter to them individually, and which they want to focus on. Maybe one cares a great deal about understanding investment strategy, whereas another is a philanthropist. Maybe one has legal training and is intrigued by the trustscape, while another is a community organizer. Each can see how their own interests and abilities plug into the Five Capitals, and therefore how, ultimately, the “family’s learning” is really just a continuation and expression of their own lifelong learning goals.

Second, as Jay Hughes as long stressed, the goal is for a family’s financial capital to support and strengthen its qualitative capitals. This does not just mean spending time and money on learning together. It means that each family member needs to find ways to use financial capital to grow as an individual, and to express their individual and family values in the world. There is a lot of spadework that must happen before this is really possible for most family members–as the lists above demonstrate. But ultimately an integrated family learning curriculum that develops each individual family member in all five of the family capitals will lead to individuals that can look out into the world, assess where they want to make a difference, and deploy their financial capital (through investment, business, or giving) to create that desired impact. Family members that are ashamed, afraid, or have otherwise not integrated their financial situation into their lives in a healthy way will never be able to do that–hence, the need for family learning. Only individuated, adult, clear-eyed, value-driven family members can take that sort of step into the world.

Finally, as mentioned above, every family member can and should augment a family’s “wealth” by increasing its human, learning, social, and legacy capital–even if that family member does not want to or know how to increase the family’s financial capital. Not everyone is an investor. And not everyone believes–particularly at this moment in history–that growing or even preserving financial capital within a family for generations is the appropriate use of a family’s financial success. These are decisions to be made by individuals and families as they work through these issues. But every family member can grow their own human capital to flourish more in the world, can grow their learning capital by pushing themselves to learn and acquire knowledge and skills, can grow their social capital by working on their own interpersonal and intrapersonal skills, and can grow their legacy capital by both connecting to their history and by envisioning what legacy they want to leave behind them. In this way, every family member, of every generation, can grow a family’s true wealth.

Thanks

I am grateful to many friends, colleagues, and mentors that have helped in the creation of these ideas. I will name only a few here: Hartley Goldstone, Jay Hughes, Ruth Steverlynck, and Christian Stewart. Each is beyond excellent in these domains and has helped me to formulate my understanding of these challenges. To all the others I am not naming specifically, you know who you are (I hope)!