The central assumption in most family enterprise books, workshops, and advice is that a business family should work to sustain its financial and human capital for multiple generations. The “great families,” we are told, think in 100-year time frames and lay plans to survive seven generations or more. “Keeping it in the family” often means propagating financial assets and handing them down to further the family’s interests over a long period of time. The last few decades have seen massive concentration of wealth into the hands of a relatively few such families, and a massive explosion of consultants and advisors (myself included) offering to help them plan for an extended, multigenerational family legacy. Family offices, private trust companies, family foundations, and perpetual trusts are all designed to preserve a family’s control of its human and financial capital for many generations.

And … in October, 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report stressing that we have 11 years–until 2030–to take dramatic global action if we have any hope of containing the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius or less. That would mean cutting carbon dioxide emissions to net zero by 2050, with CO2 emissions falling by about 45 percent by 2030. Absent such measures, the IPCC warns, we risk making the planet uninhabitable for human life. Some believe that technological fixes will extend that timeline. Others that the IPCC report actually understates the crisis, and that it is time to stop pretending that there is any hope and settle in to the reality that humanity will not be able to prevent this calamity. Despite pockets of denial, and regardless of one’s views on the exact timeline we face, the reality that the climate is changing is increasingly on the minds of the members of such business families. A 2019 UBS survey of family offices, for example, found that over 50% “consider climate change to be the single greatest threat to the world.”

I recently had a long conversation with a second (or “rising”) generation member of a family wrestling with these issues. Or, put slightly differently, with a family member wrestling with whether his family should be, but isn’t really yet, wrestling with these issues.

And in recent work with family clients, I have increasingly begun to hear such concerns raised. “Why should we be talking about how our family will be doing in 100 years, given the realities of climate change? Shouldn’t we be spending all of our financial and other resources on what really matters–stopping this catastrophe for all, not just saving them for our family?” Some have characterized this as a revolt of the millennial generation. (This is a growing conversation on its own.) But these fears and concerns seem more widespread: boomers, Gen Xers, and millennials alike are beginning to wonder aloud about what planning for their family’s future means in the era of climate change.

One Extreme Reaction: Myopic Self Interest

One possible approach, of course, is to see no conflict at all between these two priorities. If the climate is changing and humanity is threatened, all the more reason to keep as much financial wealth in the family as possible, so as to protect the family against calamity if things get bad.

I am sure that some hold this view, but I have never heard it actually expressed. It does not need be expressed explicitly, however, for this view to be present in family conversation. When a family member takes any version of a denying, minimizing, or overly techno-optimist position about climate change, it is easy for others in the family–who are more explicitly worried about climate change–to silently attribute to that person some version of this extreme view. In their heads, they tell a story that that person is myopic, selfish, or perhaps, at an extreme, morally suspect. This can be the implicit judgment in the room even if no one states the “let’s keep it in the family to protect ourselves from harm” position. Just talking about “keeping it in the family” at all can very easily seem like a diluted version of this point of view.

Another Extreme Reaction: Guilt, Shame, and Fear

At the other end of some spectrum, family members may have a very different reaction: guilt, shame, and fear. I see this in many younger family members, who are beginning to question–often quietly and to themselves–how their family’s success or lifestyle measures up in the face of climate change.

At the other end of some spectrum, family members may have a very different reaction: guilt, shame, and fear. I see this in many younger family members, who are beginning to question–often quietly and to themselves–how their family’s success or lifestyle measures up in the face of climate change.

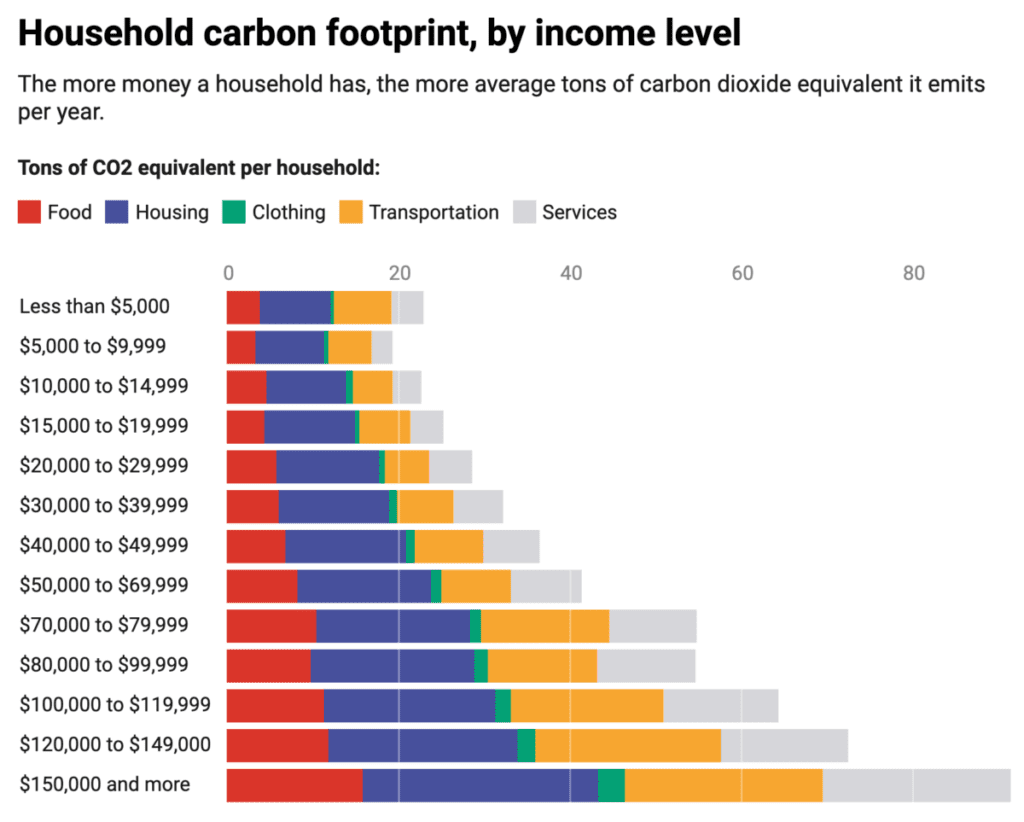

There is reason to wonder. The statistics show overwhelmingly that wealth correlates directly with carbon emissions. The average carbon footprint of the wealthiest U.S. households is over five times that of the poorest households. This is not surprising: those with more income and wealth are more able to travel, purchase new cars frequently, build new and larger houses, eat more meat, and so on. Particularly as transportation becomes an increasingly large share of global carbon emissions, the wealthy’s footprint grows.

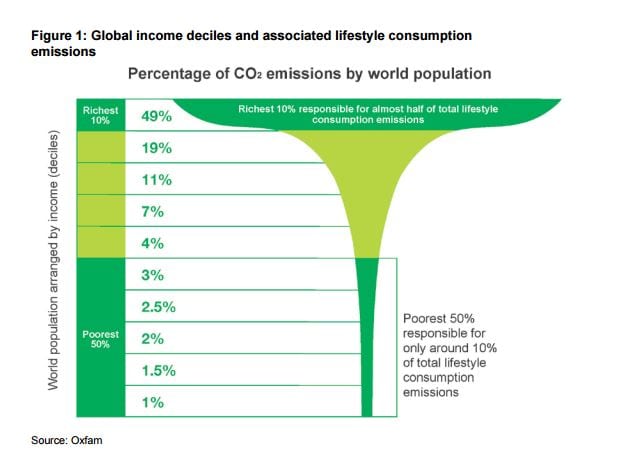

This is true at a global scale as well. Oxfam has shown that the world’s richest 10% account for roughly half of carbon emissions related to lifestyle, whereas the world’s poorest 50% account for only about 10% of those same emissions. Even more extreme, the carbon footprint of someone in the world’s richest 1% is most likely roughly 175 times the size of someone in the world’s poorest 10%.

What’s more, these wealth effects are not counteracted by personal choices to be more environmentally conscious. A recent study showed that even those with very high pro-environmental self-identity–who made many “green” choices in consumption and lifestyle–tend to have disproportionately large carbon footprints if they are wealthy. Put simply, the effects of income and wealth swamp personal pro-environmental choices. Buying a Tesla is nice, but it doesn’t overcome the frequent long-distance air travel in which the wealthy typically partake (for work or pleasure). And at an extreme, one ride on a private aircraft emits roughly 6 times more carbon per passenger than a commercial jet.

In our increasingly polarized society, these disparities have led to headlines proclaiming that “Billionaires are the leading cause of Climate Change” and “The problem with billionaires fighting climate change? The billionaires.” These sentiments are very real: as the subtitle of one of the above articles put it, “it’s great that philanthropists are pouring money into environmental causes. But it would be better for the planet if billionaires didn’t exist at all.”

All of this rhetoric is relatively new–and extremely difficult for some members of wealthy families. The response can be paralysis caused by extreme guilt, shame, and fear. In some families, inheritors know that their wealth-creating ancestors worked directly in fossil fuels, such as in the oil and gas industry, and this may cause personal emotional turmoil. In many families, a diversified portfolio will be at least partly invested in the energy sector, which some in a family may increasingly dislike or reject. And in all enterprising families, even absent a direct link in the family’s business history to the energy sector, some inheritors may feel that their family’s contribution to general economic growth–through whatever industry–has been a net negative for the planet. Rather than celebrate their family’s success (for creating jobs or producing innovation, for example), some family members may now question whether the economic growth that their family contributed to (and was rewarded for) was worth the associated ecological costs.

And In Between …

Again, this shame, guilt, or fear need not be expressed aloud to be in a family conversation. Any articulation of climate change concerns can be heard by another family member as a rejection of the family’s legacy, ancestors, business success, material wealth, or lifestyle choices, even if the person bringing up climate change may not be trying to criticize the family so completely. Family members that have worked their entire lives building the family enterprise, for example, may bristle at the implicit (or explicit) attack on their choices and identity that they sense in climate change conversation. Particularly if those raising these issues are clumsy with their comments, they can unintentionally invoke an extreme reaction. Even with skill and care, these are hard conversations.

In between (or in addition to) these two extreme positions lie the full spectrum of today’s climate change opinions. Some continue to deny completely that human activity is causing climate change. Others have abandoned that position but stake out ground nearby, claiming that “it is complicated,” “the science is less clear than people say,” “there are probably multiple causes,” or “it’s too early to know.” Or they may accept that climate change is real, but scoff at the idea of harming the economy by taking political or personal action to combat it. They may defend their personal or family business history, regardless of the industries reflected therein, or their right to invest in any profitable business, regardless of its carbon impacts.

And then there are the many that accept that climate change is occurring, believe that carbon emissions are the cause, and are convinced that a crisis is upon us–but feel helpless or overwhelmed by the situation or have chosen to do little in response. Perhaps they make some pro-environmental lifestyle choices, such as recycling, installing solar panels, or driving an electric car. They may even purchase carbon credits to offset their travel. (The wealthy are particularly able to afford such lifestyle modifications that permit a pro-environmental identity without much tangible lifestyle sacrifice.) But they continue to fly around the world on vacation, build-to-suit a luxury home, or otherwise maintain their lifestyle in ways that counter any effort they’ve made to reduce their carbon footprint. Further, in a wealthy or business family, they may not have considered divesting their portfolio of energy stocks or the possible value of impact investing in enterprises seeking to combat climate change. Nevertheless, and importantly, the large number in this category may consider themselves environmentalists and may argue that they are very concerned about climate change.

Finally, there are those that have changed their lifestyle and their investments, are politically engaged trying to combat climate change, and are vocal about these choices. In enterprising or wealthy families, these family members may be quite countercultural. They may live differently, read different books, and vote differently than the rest of their family–including than those in the just-mentioned category that see themselves as pro-environmental. They may prioritize responding to climate change as their first concern, which may seem extreme or absurd to others in their family but completely obvious and foundational to them. They may feel tremendous guilt or doubt about their family’s choices, and have deep reservations about any planning for preserving the family’s enterprise or wealth into the future rather than deploying it–through investment or giving–to combat the climate crisis.

Talking About These Issues is Complex, but Possible

Many business families may avoid these topics because of the inherent difficulty created by these very different viewpoints. Imagine how challenging, for example, it would be for the wealth creator, or for members of the family working in a family business, to hear that the family’s business history is morally suspect because it contributes to the carbon economy? Such a position could easily seem ungrateful, disloyal, and/or hypocritical, particularly if voiced by someone that has benefited from the family’s economic success. Conversely, a family member deeply committed to combatting climate change–and making serious personal lifestyle sacrifices to try to make a difference–may feel that even being asked to fly across the country to attend a family meeting is a request to abandon their deepest values.

There are, of course, some families that enjoy complete internal consensus about these issues and therefore have no conflicts to explore or manage. It is the far larger number of families in the middle, however, that must grapple with talking through the implications of climate change for multigenerational family enterprise or family wealth. If even one family member diverges from the family’s norm–or if there is a plurality of views in a family, with no “norm” at all–then these issues are most likely beginning to bubble to the surface or are being kept just below it.

Unfortunately, too often any attempt to surface or discuss differing views will descend quickly into stereotypes and labels: “climate denier” versus “limousine liberal.” Even when the positions held are more nuanced, family members may retreat to two extreme “sides” in a debate, simplifying away the complexity of others’–and their own–views.

I have written elsewhere on this site about the importance of families being able to unpack even the most stringently partisan perceptions. There I used the relatively benign example of a family’s perception of in-laws versus an in-law’s perception of a business family. But these climate change positions are obviously far more entrenched, difficult, emotional, and identity-implicating. Talking about how and whether climate change should influence a family’s plans for the future, use of its financial resources, investment choices, and charitable giving requires a much greater level of commitment to each other and interpersonal skill than almost any other conversation I can imagine. It offers great benefits as well, however, particularly as an antidote to the polarization and distance that can be created by avoiding these difficult issues.

This Isn’t Left versus Right or Us versus Them–It is Us versus Us

As a first step towards such conversations, I will start with one piece of advice: they will not succeed if framed as left versus right or us (climate activists/climate change skeptics) versus them (climate change skeptics/climate activists). The reason is that such antagonistic framing overly simplifies the complexity of these conversations, and of the people having them.

As far as I can see, almost everyone is at this point caught in the same challenge vis-a-vis climate change: deep internal ambivalence, conflict, and turmoil. The most fervent climate activist, who would love to argue purely for a radical shift in the economy and end to fossil fuel use, probably flies on airplanes, drives a car, and makes other compromises she quietly questions. In addition, she may silently fear the potential economic disruption of more radical climate policies, or privately wonder whether technological innovations are, indeed, our greatest hope, rather than individual and collective behavior change. She may have doubts about whether a “replacement economy” is really viable, or even desirable.

Similarly, the most vocal climate skeptic at this point may privately fear the mounting evidence of the ongoing trauma being created by climate change, and may admit that it is already having very real economic impacts that cannot be ignored. Billions of dollars are being spent to repair bridges and roads washed out by flooding, towns and homes destroyed by fire, and so on. Increasingly, those in corporate board rooms are focusing on the economic implications of the changing climate, whether because insurance markets are freezing up in certain parts of the country or world, or because it becomes increasingly difficult to invest capital wisely in the face of such deepening ecological uncertainty and disruption.

It is immensely valuable to connect honestly to this ambivalence and uncertainty. No one has “the answer” to climate change. And no member of a family has a monopoly on good ideas about how their family should respond to this evolving situation. Almost everyone is conflicted, uncertain, anxious, somewhat guilty, and afraid.

Conversations That Need To Happen

If they can learn to talk authentically about their nuanced positions and views on this complex subject, family members will discover that they have a lot to learn from, and a lot to give to, each other. There are generational, geographic, gender, political, spiritual, and other differences to explore. What follows are some thoughts on several critical conversations that enterprising families can and should begin. I believe that these conversations should be on the agenda of most business families.

What Do We Believe About Climate Change, and How Has It Impacted Our Lives? The first conversation I would recommend has two components: sharing each family member’s perspective on climate change, and sharing each person’s feelings about or responses to what they perceive is happening. The first step is for each family member to share their perspective as openly, honestly, and authentically as they can, in a controlled or structured setting that allows for different opinions without condemnation or counterargument. In any family with widely diverging views, this will most likely require a skilled facilitator who can shape the discussion and make it productive. It also requires that family members come to the conversation with a shared goal of learning about others’ views, even if very different from their own.

What if that goal is not shared, and some family members do not want to have these conversations or listen to others’ opinions? To a certain extent, there is no forcing such a conversation. But there is a meta-conversation to be had if some family members are reluctant to try really listening to each other: if we cannot, as a family, discuss something as monumental as a potential threat to the planet at this scale, how can we consider ourselves prepared to deal with any threat to our family’s wellbeing?

I have written elsewhere about the importance of a family developing all five types of capital: human, learning, social, legacy, and financial. To avoid talking about an issue as potentially important and threatening as climate change undermines all five of these capitals. It ignores what some in the family may view as the most profound, existential threat to their, and their descendants’, well being (human capital); it flies in the face of a family’s commitment to learning, seeking out information about internal and external threats, and staying fully informed to excel in a challenging world (learning capital); it most likely will strain relationships by avoiding needed conversation and short circuiting potential decision-making (social capital); it bypasses a potentially deep conversation about the family’s legacy, vision, and purpose going forward, as well as potential conflict over giving priorities or strategy (legacy capital); and it overlooks that whatever happens, the future of the Earth’s climate and ecology has profound implications for a family’s financial stability (financial capital).

Perhaps the last of these is the most poignant. Some family members may not want to discuss climate change, asserting that to consider altering the family’s business or investments would risk the family’s financial wealth. But this, of course, begs the question: what if the threat is real, and the family fails to assess that threat sufficiently? Any family hoping to preserve its human and financial capital for generations must actively seek information about the most pressing threats it faces–whether from war, economic collapse, or, in this case, potential environmental crisis. Only by looking around the next corner do successful families stay successful over long periods. If a family is really serious about its future and legacy, how can it not engage in serious discussion of its members’ views on climate change?

This reasoning may not persuade all family members that such discussion will be worthwhile, but it at least attempts to tie such conversation to the higher-order goals or values that many enterprising families have set for themselves: to preserve human capital, to be a learning family, to have open and honest communication and build social capital, to preserve their legacy into the future. It is difficult to square these goals and values with refusal to try to discuss climate change.

To repeat, this first conversation–and all of these conversation topics–should not be about reaching agreement, or about “who’s right” or “who’s wrong” about climate science. It should simply be an opportunity for all members of a family to share their views, concerns, fears, and feelings. That, in itself, may be a profound step for most business families.

How Has Climate Change Impacted Our Lifestyle Expectations, Including Feelings About Whether to Have Children? A second topic for discussion are the lifestyle choices that family members may have already made, and the expectations they may have about what their future will hold. This includes the question of whether family members expect to have children–and whether their views on climate change affect their choices about this issue.

Boomers and GenXers may not relate to the idea that fear of the future would lead a Millenial or GenZ to decide against children, but it is increasingly common to hear younger family members express such views. The UK-based BirthStrike movement, for example, registers and promotes women and couples that have made this decision. Similarly, the US-based Conceivable Future stresses that the climate crisis is also a reproductive justice crisis that is limiting reproductive choice. These views have received a great deal of press attention.

These topics are obviously intensely personal and potentially painful. But if a family is committed to learn from each other across generations and viewpoints, these lifestyle and reproductive impacts of climate change deserve to be voiced and heard. Again, the goal cannot be to argue anyone out of such personal decisions, or to correct their “incorrect” views. Instead, these are opportunities to deepen relationships, hear each other, and understand how climate change fears may be impacting members of a family in ways that have not previously been surfaced.

These issues could be important for any family, but may be particularly relevant in a multigenerational business family. Often such families have intricate estate plans, trust structures, and governance mechanisms that were constructed under the assumption that most descendants would in turn have further children of their own. If a family member–or an entire generation–were to choose otherwise, such plans may be woefully inadequate. Similarly, lifestyle choices–particularly decisions to restrict spending and live more humbly–may be important for trustees (or others making discretionary distributions) to understand.

Should We Divest From Certain Carbon-Intensive Industries? Just as personal, and just as potential sensitive, is the question of divestment.

The fossil fuel divestment movement was largely begun by 350.org, which has promoted it since 2012. Some well-known families have publicly divested from the fossil fuel industry. Descendants of Lauren Drake, the past president of Standard Oil, recently did so, as have the Rockefellers (at least from their family foundation).

Divestment can be an extremely sensitive topic, particularly in families whose history is in the energy sector. Some analysis shows that divestment from fossil fuels will not damage a diversified portfolio’s return, and is therefore relatively easy as a practical matter. Nevertheless, talk of divestment may strike some family members–particularly a wealth creator or business leader–as “tying one’s hands behind one’s back.” Particularly if even some of a family’s business success has been in the energy sector, divestment may be emotionally fraught.

But there may be common ground in such conversation as well. Everyone in a business family may agree that decisions about whether to invest–or divest–from a given industry or opportunity should be fully informed. This suggests that at the very least the economic and political risks of climate change–if not the ecological risks–should be factored into any decision to retain oil and gas investments. If current models are correct–an “if” some family members may dispute–it seems as if ecological change is occurring much quicker than predicted. This may, in turn, lead to rapid economic or political shifts, which may radically alter the risk/return profile of energy sector investments in unexpected ways.

Beyond this rather pragmatic stance, of course, lie the environmental, moral, and even spiritual reasons that family members might want to divest a family business or portfolio from carbon-intensive industries. My point is not that pragmatic, economic argument should dominate, but that it provides at least a basic foundation on which to build conversation. If everyone can agree that analyzing the economics of climate change is worthwhile, perhaps a family can, in turn, broaden that divestment conversation into the more intangible impacts that certain family members may feel from holding fossil fuel investments.

Should We Be Impact Investing? Bill Gates and others have argued that divestment is unlikely to impact carbon emissions or climate change, and that climate-related impact investing–channeling investments towards alternative energies and other potentially helpful disruptive technologies–is more likely to make a difference. The argument is simple: the existing energy sector will continue to find the capital it needs to survive (or, put differently, divestment is unlikely to starve it in any significant way), whereas innovators can truly benefit from investment support, particularly in their early stages. Thus, impact investing is a separate conversation from the decision to divest (although most families that do one will likely do the other).

Impact investing is certainly not new, but it is new to many enterprising families. And, like climate change, it generates strong feelings, very disparate viewpoints and beliefs, and intense argument that sometimes descends into untested assumptions or oversimplifications. I do not have the space here to discuss all of the complexities of impact investing, but I will highlight some of the common touchy subjects it raises:

- What are the economic costs and benefits of impact strategies?

- Should a family be willing to accept lower returns in an impact investment than they expect elsewhere, and if so, how to think about that decision?

- What if the family does not have consensus on its motivations for engaging in impact investing?

- Is “not doing” certain things good enough, or should a family more proactively invest to promote the industries, innovations, and entrepreneurial ecosystems it thinks are needed?

As with all of these climate change topics, to discuss these questions may require family members to manage strong differences of opinion. There are many plausible positions on which family members can diverge. One might be against divestment or impact investing; another willing to divest but not committed to proactive impact capital deployment; and a third focused far more on promoting innovation through impact investing than on divestment. Each may think their own position obviously right, and question the others. Again, a skilled facilitator may be needed to work through the ins and outs of these conversations.

Should Climate Change Be Part or All of our Philanthropic Focus? The final needed conversation centers on philanthropic efforts. Many enterprising families support diverse charitable projects: their church or other religious institution, local community organizations (e.g., a food bank, shelter, community center, museum or arts organization, hospital, etc.), health-related causes (particularly if a family member has been affected), an alma mater, and so on. The family may have deep roots into their community and long ties to these institutions. Its reputation and family name may be intricately linked to its history of support for or its leadership of a charity board. All of these nuances may make shifting its philanthropic priorities difficult and full of implications for the family’s sense of who it is and what it is known for. For many families, there is nothing more closely tied to the family’s sense of identity and legacy than its philanthropic focus.

And, some family members may believe that climate change should fundamentally change that focus. All other philanthropic priorities might seem to pale by comparison if one sees an existential threat and fears for the safety of not just one’s family but all life. How could anything take precedence over that sort of need? For a family member deeply committed to altering their own lifestyle, changing their investment priorities, and otherwise reforming their carbon footprint, it may seem entirely obvious–really, beyond question–that they should also reorient their, and potentially their entire family’s, charitable contributions and efforts.

I have heard multiple family members layer an additional complexity on to this general impulse. In those families that created their wealth in carbon-intense industries such as the energy sector, or that continue to invest in those domains, some family members may feel that directing philanthropic giving towards climate change efforts is important to compensate for the harm the family has caused or is causing elsewhere. “If we won’t divest,” the argument goes, “at least we should be giving to soften the impact we’re having.” Other family members may bristle, of course, at the suggestion that any compensatory step is needed–or at the basic idea of abandoning long-held philanthropic priorities for this new cause.

Should We Support Political Action on Climate Change, And What If Some Family Members Do and Others Do Not? Ultimately, divestment, impact investing, and philanthropy may not be enough: climate change most likely requires concerted political action, nationally and globally, to effect change at sufficient scale and pace. As my friend Matt Wesley has pointed out, were Bill Gates to give away his entire fortune tomorrow, it would only keep the New York City public school system operating for 2-3 years. To turn the world’s economy as rapidly as climate change may require, politics, not philanthropy, is probably required.

Like the other conversations already discussed, this one is fraught. It has one additional complexity, however. In some families, each family member may feel entirely free to support whatever political causes they wish. In others, however, if a small number of family members supported political action on climate change (through donations or otherwise), others might object on the grounds that such support could cause problems for the family’s business. Imagine, for example, a family invested in the energy sector that was simultaneously perceived to be advocating against that same industry. Those in the family business might complain that their efforts were being undermined by other family members; those engaged in climate change activism might object to any infringement of their autonomy or right to support political causes of their choosing. Again, no easy answers.

Ending Up in One Piece

Although I have spent a good portion of my professional life working with business families on conflict and difficult conversations, I do not have easy answers to guarantee that these discussions will go well. As trite as it may sound, the key is listening. There are lots of resources available to educate yourself and your family about the science and the facts. Ultimately, however, the issue for a business family isn’t really whether it can reach consensus on the “facts.” It’s whether they can do so in one piece, or, better yet, whether they can get deeper than facts and begin to talk about their varying world views of, feelings about, and reactions to climate change. Rather than reach agreement, as a first step these families must simply be willing to explore the deep divide they may find between family members on the how the family’s future should or should not be impacted by climate change.

Ultimately, of course, decisions need to be made and action taken–whether that means choosing to divest or invest differently, or choosing not to do so. I do not pretend that these will be easy decisions for any family. My purpose here has merely been to open up the issues for family wealth that climate change creates, and to encourage family members to begin to try to talk through these difficult conversations.

In my view, these conversations are critical, not just because of the global issues at stake, but for the health of any modern business family. If there are diverging perceptions and beliefs, use them as an opportunity to deepen your understanding of each other and build the family’s relationships. If there are strong emotions and difficult identity issues at stake, get coaching so that these can also be discussable together. If there are financial implications of your discussions, face them with clear eyes. A “great family” is one that can assess threats, reach decisions, and move forward. Climate change may well be the central test of enterprising families over the next century. However families choose to react to that test, doing so openly, honestly, and in concert will help them, and others, far more than avoiding these admittedly difficult topics.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash